“What are you hiding there, Mother?” asked the small child, looking curiously at the strange cloth that was always wrapped around his mother’s waist.

In the small village in Ethiopia, under the scorching sun, that mysterious bundle was constantly fastened to his mother’s waist.

“There’s earth here,” she answered simply.

When she gently opened the fabric, the child’s eyes widened in wonder. “Just earth? Why are you carrying it?”

A soft smile appeared on her face. “This isn’t just any earth, my child. This is earth from Jerusalem.”

I heard this story several years ago when I picked up a young hitchhiker. During the drive, he told me about his childhood, about his mother, and about the mysterious bundle that accompanied her all her life.

“One day,” he said, “a man came to our village claiming he had a treasure in his hands—earth from the Holy City. People stood in line to hold, if only for a moment, a bit of the holy soil. My mother, a simple woman who could barely read or write, took out all her savings to buy a small amount of this earth. Was it really earth from Jerusalem? Who knows. But for her, every grain was worth gold.”

“And where is your mother today?” I asked him. “Is she here in Israel?”

His voice broke slightly as he continued: “My mother never merited reaching Jerusalem. She passed away in Ethiopia and was buried on the outskirts of our village. But before her death, she requested one thing: that they bury her with this earth. That a small piece of Jerusalem would be with her forever.”

The People Time Forgot

For more than 2,700 years, a Jewish community lived in the mountains of Ethiopia, cut off from the rest of the Jewish world. They called themselves Beta Israel—the House of Israel. Their neighbors called them Falasha—exiles, strangers. But they knew who they were. They were descendants of the Tribe of Dan, exiled by the Assyrian conquest in 722 BCE when the Ten Tribes were scattered.

The prophets knew about them. Isaiah spoke of their exile and their eventual return: “And it shall come to pass in that day, that the Lord will set His hand again the second time to recover the remnant of His people… from Assyria, and from Egypt, and from Pathros, and from Cush” (Isaiah 11:11). He described exactly where they would be: “Woe to the land of the whirring of wings, which is beyond the rivers of Cush… At that time shall a present be brought unto the Lord of hosts from a people tall and smooth… to the place of the name of the Lord, to mount Zion” (Isaiah 18:1-7).

Zephaniah echoed this promise: “From beyond the rivers of Cush… they shall bring My offering” (Zephaniah 3:10).

But between those ancient prophecies and their fulfillment stretched nearly three millennia of isolation, persecution, and unwavering faith.

A Kingdom in the Mountains

The Beta Israel community didn’t just survive in Ethiopia—for centuries, they ruled. Between the fourth and seventeenth centuries, a Jewish kingdom existed in the Simien Mountains of northern Ethiopia. They called it the Kingdom of Gideon, because many of its kings bore that name. The mountains became their fortress, peaks reaching over 15,000 feet above sea level, shrouded in mist and cloud. Some rabbis would later identify these as the “mountains of darkness” mentioned in the Talmud, beyond which the ten tribes were exiled.

In 325 CE, the Ethiopian emperor declared his empire’s conversion to Christianity. The Jews refused. What followed was a civil war that lasted two hundred years. The Beta Israel retreated to their mountain strongholds, establishing settlements at heights of 6,000 to 10,000 feet to avoid malaria, hostile tribes, and Christian persecution.

For over a thousand years, they fought to maintain their faith and their independence. In the tenth century, Queen Judith of Beta Israel conquered the Christian capital of Axum and ruled all of Ethiopia for forty years. Arab historians recorded her victories. The Axumite king fled before her armies. Every Christian symbol in the kingdom was destroyed.

But the wars never truly ended. Century after century, Christian crusades pushed against the Jewish kingdom. By 1625, the last Jewish stronghold fell. The final King Gideon was exiled. Jewish lands were seized and given to the church. Those who refused to convert lost everything—their farms, their homes, their citizenship. Many became blacksmiths, weavers, and potters, craftsmen without land.

The Christians called them Falasha—the people without a country. But they never forgot who they were or where they belonged.

Beyond the Sambatyon

In the ninth century, a Jewish merchant named Eldad the Danite appeared in North Africa. He claimed to come from the Tribe of Dan dwelling “beyond the rivers of Cush.” The Jews of Kairouan were astounded. He spoke only Hebrew, not Arabic or the languages of Africa. He knew nothing of the Talmud or rabbinic literature. When asked about Jewish law, he replied simply: “Thus we learned from Joshua, from Moses, from the Almighty.”

He told them about the Sambatyon River, the legendary barrier beyond which the ten tribes were exiled. “And that river still rolls stones and sand without water with great noise and great sound,” he explained. “And the river rolls stones and sand without any drop of water all six days of the week, but on Shabbat it rests.” The river surrounded his people, preventing them from returning to the Land of Israel.

Was Eldad telling the truth? The rabbis debated. But his description matched what they knew from the Midrash about the exile of the ten tribes. And if the Nile and its tributaries were the “rivers of Cush,” then Ethiopia sat precisely where the prophets said the exiles would be found.

Devotion in the Darkness

What made Ethiopian Jews extraordinary wasn’t just their survival—it was their devotion. Cut off from rabbinic Judaism, they preserved what they could from the Written Torah alone. They offered animal sacrifices as commanded in Leviticus. They observed Shabbat with fierce dedication. They maintained strict purity laws. They fasted and prayed. And they never stopped believing they would return.

In the 15th century, a Beta Israel leader named Abba Sabra wrote that keeping the Sabbath overrides even saving life—a ruling more stringent than rabbinic law. He established a uniform prayer text for all Jewish communities in Ethiopia. In response to constant Christian threats and forced conversions, he instituted a complete prohibition against touching a gentile. The community withdrew further into itself, building walls of separation to survive.

Rabbi Eliyahu of Ferrara wrote in 1435 about testimony from a Jew who escaped the Ethiopian Jewish kingdom: “They are masters of themselves and not under the authority of others, and around them is a great nation called Habesh who are Christians, and they are always fighting with them… Those Hebrews have a language of their own, neither Hebrew nor Arabic, and they have the Torah and oral interpretation of it, but they have neither the Talmud nor our legal decisors.”

The wars and persecutions took a terrible toll. At the end of the 17th century, about one million Beta Israel Jews lived in Ethiopia. By the beginning of the 19th century, fewer than 350,000 remained. By its end, only 120,000 survived. Many were forcibly converted. Christian soldiers would raid Jewish villages and massacre those who refused baptism. The community that remained called the forced converts “Falash Mura”—Jews who changed their religion, usually at sword point, to stay alive.

The Failed Exodus

In 1862, a Beta Israel leader named Abba Mahari Sutael reached a conclusion. Prayer wasn’t enough. They had to act.

He sent emissaries to every Jewish settlement in Ethiopia, compiled the names of everyone ready to make the journey, and set out at their head. The plan was simple but audacious: cross the Red Sea as their ancestors had in the Exodus from Egypt, then continue to the Land of Israel.

Thousands joined him. They walked for months through harsh terrain, winter storms, hunger, and disease. Many died along the way. But they pressed forward, sustained by faith and the promise of Jerusalem.

When they finally reached the shore of the Red Sea, Abba Mahari raised his staff like Moses had done millennia before. He waited for the waters to part.

They didn’t.

The sea remained impassable. After waiting and praying, Abba Mahari recognized that the time had not yet come. The devastated masses turned back to Ethiopia.

Yet Beta Israel tradition doesn’t remember this as a failure. They see it as the moment everything changed—the transition from passive waiting to active pursuit of redemption. “What Abba Mahari saw was for the future,” they explain. “They did not merit to arrive. Through their merit, we arrived.”

The World Awakens

It took another century, but slowly the Jewish world began to respond.

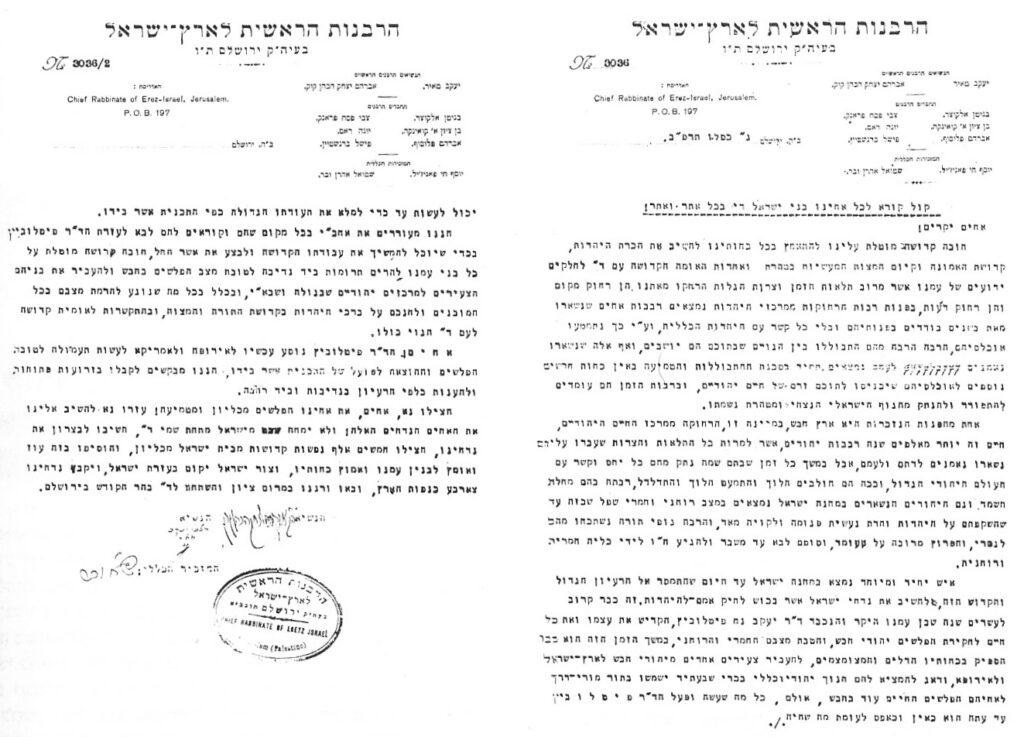

In 1866, the Chief Rabbi of Turkey published “A Call to Aid the Children of Israel in the Land of Cush,” declaring that Ethiopian Jews were no different from any other Jews of the diaspora. Aid missions began reaching the isolated communities.

But catastrophe struck again. In the second half of the 19th century, seven consecutive years of drought, war, and plague devastated Ethiopia. They called it “the Evil Time.” Two-thirds of the Beta Israel community perished.

In 1908, 43 rabbis from around the world sent a letter to the surviving Beta Israel Jews: “We your brothers will do all that is in our power to hasten help to you and to provide you with teachers and books so that your children may learn to fear the Lord alone, and we shall all merit and He will bring us to Jerusalem His city with everlasting joy.”

In 1921, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, soon to become the first Chief Rabbi of the Land of Israel, joined other rabbis in a plea: “Please save, brothers, our Falasha brothers from destruction and assimilation. Please help to return to us these distant brothers so their name will not be erased from Israel under God’s heavens.”

But bureaucracy and indifference delayed action. The Zionist leadership before and after Israel’s establishment showed little interest in bringing Ethiopian Jews to the Land. Some questioned whether they were really Jews. The few who managed to reach Israel in the 1930s through 1970s—never more than several hundred—sometimes faced deportation orders from the Interior Ministry.

Everything changed in 1973 when Rabbi Ovadia Yosef became Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel. A Beta Israel leader named Qes Barhan Baruch had sent an urgent request for recognition of his community’s Jewishness. Rabbi Ovadia’s ruling was unequivocal: “I have decided that in my humble opinion the Falashas are Jews who must be saved from assimilation and intermarriage, and their immigration to the Land must be hastened, and they must be educated in the spirit of our holy Torah and included in building our holy Land, and the children shall return to their borders.”

In 1975, the Law of Return was finally applied to Beta Israel. The way was opened.

But the situation in Ethiopia was deteriorating. Civil war had erupted, a Marxist regime seized power, and starvation spread across the country. The Beta Israel communities faced conditions worse than anything in their long history of suffering.

Operation Moses

In 1984, something extraordinary happened. Over several weeks, Israeli military and intelligence operatives coordinated a massive covert airlift from refugee camps in Sudan. Ethiopian Jews had been walking for weeks through the desert, fleeing war and famine, many dying along the way. Those who survived reached camps in Sudan, where Israeli agents arranged secret flights to Europe and then to Israel.

Almost 7,000 Beta Israel Jews were rescued in what became known as Operation Moses. When news of the operation leaked, the Sudanese government shut it down. But by then, thousands had already reached the Land their ancestors had yearned for across 2,700 years.

The Ethiopian Jewish children who survived that journey later sang about it: “Moonlight, hold on / Our food sack is lost / The desert doesn’t end / Howls of jackals / And my mother calms my little brothers: / A little more / A bit more / Soon we’ll be redeemed / We won’t stop walking to the Land of Israel.”

In 1989, Beta Israel leaders succeeded in concentrating most of the remaining Jewish community in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. The rural Jewish presence in Ethiopia, which had lasted over two thousand years, came to an end. They gathered in camps around the capital, waiting and hoping.

The Final Exodus

On November 21, 1984, Israel began a historic mission to airlift thousands of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. This initiative, known as Operation Moses, rescued nearly 8,000 people and was the first of two covert missions of its kind. The second, Operation Solomon, took place in 1991… pic.twitter.com/2UwUgSKbis

— Humans of Judaism (@HumansOfJudaism) November 19, 2025

On May 24, 1991, Israel executed Operation Solomon. In 36 hours, 35 Israeli aircraft flew continuous missions to Addis Ababa and brought 14,087 Ethiopian Jews to Israel. The Ethiopian government, on the verge of collapse in a civil war, agreed to allow the Jews to leave in exchange for $35 million, which American Jewry quickly raised.

Planes designed to hold 200 people carried over 1,000. They removed seats to fit more passengers. One plane landed with over 1,100 people aboard. On that flight, two babies were born—the first Israelis in a family line that stretched back nearly three millennia.

Within days, the ancient Ethiopian Jewish exile was over. The people who had lived “beyond the rivers of Cush” had come home. The prophecy Isaiah spoke 2,700 years earlier had been fulfilled.

The Gathering That Never Ended

Today, about 175,000 Israelis trace their roots to Ethiopia. Nearly half were born in Israel—sabras whose parents or grandparents walked through deserts carrying nothing but hope and a few possessions.

They brought with them a tradition called Sigd, observed fifty days after Yom Kippur each November in Jerusalem. The word means “prostration.” On Sigd, Ethiopian Jews would gather on a mountaintop in Ethiopia, read from the Torah, and pray facing Jerusalem—the city they believed they would one day reach. The day commemorates the Jewish people’s acceptance of the Torah and their longing for return to Zion.

Now they observe Sigd in Jerusalem itself, gathering on the Armon Hanatziv promenade overlooking the Old City and the Temple Mount. They prostrate themselves in prayer not toward Jerusalem but in Jerusalem, at the place their ancestors dreamed of for 130 generations.

The woman who carried Jerusalem’s earth around her waist—the mother in that story—never reached Israel. But her son did. And his children were born here. The earth his mother cherished, which may or may not have truly come from the Holy City, was buried with her in Ethiopia. But her son’s children walk on the actual stones of Jerusalem every day.

What Was Lost and Found

The story of Ethiopian Jewry reveals something we might otherwise miss about the nature of exile and redemption. Most Jewish communities maintained connection with each other, even across vast distances. Rabbis wrote letters back and forth, travelers brought news from one community to another, books were copied and circulated, and traditions were continuously shared, debated, and refined through ongoing contact.

The Beta Israel community had none of this. They lived in complete isolation, preserving what they could from memory and from the Written Torah alone.

To understand what this means, you need to grasp when they were exiled. The Assyrians conquered the northern Kingdom of Israel and exiled the ten tribes in 722 BCE—more than a century before the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE. The Beta Israel community descended from those exiles, primarily from the Tribe of Dan. They left before most of the events that would shape rabbinic Judaism.

They never knew about Purim because the story of Esther happened during the Babylonian exile, after they had already been gone for over a century. They never knew about Chanukah because the Maccabean revolt occurred in 165 BCE, more than 550 years after their exile. They had no knowledge of the Mishnah, compiled around 200 CE, or the Talmud, completed centuries later. They knew nothing of Rashi, who lived in 11th century France, or Maimonides, who lived in 12th century Egypt and Spain.

What they had was the Torah itself—the five books of Moses. They observed Shabbat based on what was written in Exodus and Deuteronomy. They offered sacrifices according to the detailed instructions in Leviticus. They circumcised their sons as commanded to Abraham. They studied the written word and passed it down from generation to generation without any of the rabbinic interpretation and development that occurred after they were exiled.

Technically, we shouldn’t even call them “Jews.” That word comes from Judah, the southern kingdom and the tribe from which most modern Jews descend. The Beta Israel community descended from Dan, one of the northern tribes. They are Israelites—children of Israel—which makes them Israelis in the fullest sense of that word, both ancient and modern. They are the House of Israel, Beta Israel, as they called themselves.

When Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and other rabbinic authorities confirmed their Jewishness, they were recognizing that Jewish identity runs deeper than knowledge, deeper than books, deeper than institutional connection. The Beta Israel community proved that a people cut off from all Jewish learning and all Jewish community for 2,700 years could still preserve the essential core of who they are.

But there’s something else their story reveals. When the prophets spoke of gathering the exiles, they weren’t speaking metaphorically. Isaiah wasn’t using poetic language when he described people from “beyond the rivers of Cush” returning “to the place of the name of the Lord, to mount Zion.” Zephaniah wasn’t engaging in literary flourish when he prophesied that “from beyond the rivers of Cush… they shall bring My offering.”

They were describing exactly what happened beginning in 1984. The lost tribe came home. The people beyond the Sambatyon returned. The Jews of the mountains of darkness walked into the light.

A Present Brought to Zion

The Ethiopian Jewish community brought with them more than their physical presence. They brought a different perspective on Jewish tradition—one shaped by isolation but also by devotion, by persecution but also by dignity, by poverty but also by pride.

They brought their own approach to Jewish law, preserved without Talmudic influence. They brought their practice of offering sacrifices, which a small number continue in modified form to this day. They brought their ancient liturgy. They brought stories and songs and prayers unknown to the rest of the Jewish world.

And they brought their unwavering faith that God had not forgotten them, that the covenant remained intact, that Jerusalem still called to them across mountains and deserts and centuries.

Isaiah prophesied that they would bring “a present” to Mount Zion (Isaiah 18:7). That present was themselves—the living proof that God keeps His promises, that exile however long does eventually end, that the scattered can be gathered, that those who seem lost forever can still be found.

When you see Ethiopian Jewish families in Jerusalem today, when you hear them speaking Hebrew mixed with Amharic, when you watch them celebrating Sigd on the overlook facing the Temple Mount, you’re watching prophecy fulfilled. Not symbolic prophecy. Not spiritual allegory. Literal, physical, flesh-and-blood prophecy—ancient words spoken by Isaiah and Zephaniah becoming visible reality before your eyes.

The woman who carried earth from Jerusalem around her waist, who saved for years to buy a few handfuls of dust, who asked to be buried with that earth because she couldn’t reach the city itself—she didn’t live to see the fulfillment. But her faith was vindicated. Her devotion bore fruit. Her son and grandson walk the streets she could only imagine.

In that sense, the earth she carried and the earth beneath her son’s feet in Jerusalem today are the same. Both represent a connection that exile couldn’t sever, that time couldn’t erode, that persecution couldn’t destroy.

The lost tribe of Dan returned. The people beyond the rivers of Cush came home. The prophecies spoken in judgment became promises fulfilled in mercy.

And every Ethiopian Jewish child born in Israel today is living proof that God sees exile as temporary, that distance doesn’t mean abandonment, that even 2,700 years of silence doesn’t mean the covenant is void.

They walked to the Red Sea and it didn’t part. But a century later, planes came and carried them over it. Sometimes redemption comes differently than expected. Sometimes the miracle takes longer to arrive than we think it should. But it comes. The gathering continues. And the children of Cush have finally, definitively, come home.