A remarkable archaeological discovery has recently been published in the peer-reviewed journal Atiqot, revealing new insights into the commercial life of ancient Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. The find, a Hebrew inscription on a stone fragment bearing what appears to be a financial record, offers an unprecedented glimpse into the everyday economic activities that took place along one of Jerusalem’s most important ancient thoroughfares.

The discovery was made during excavations carried out on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority in the City of David, within the Jerusalem Walls National Park, and funded by the City of David Foundation. The research was conducted by Nahshon Szanton, Excavation Director for the Israel Antiquities Authority, working in collaboration with Prof. Esther Eshel, an epigraphist from Bar-Ilan University, whose expertise in ancient Hebrew inscriptions proved crucial to understanding the significance of this find.

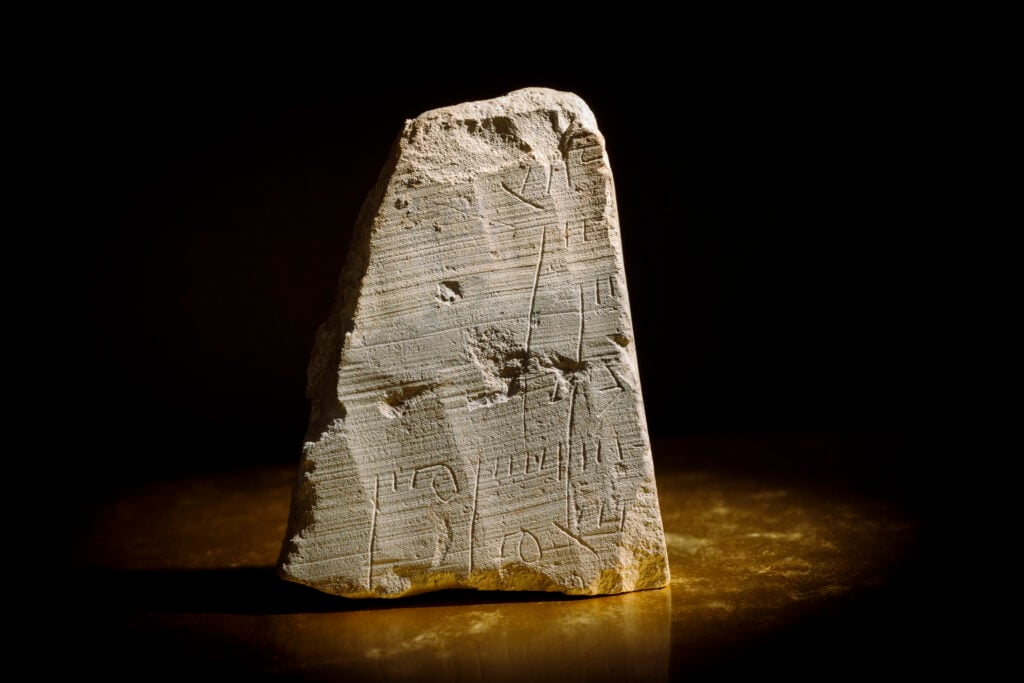

The centerpiece of this discovery is a small fragment of a stone tablet bearing an inscription that was produced for financial purposes. The seven partially preserved lines include fragmentary Hebrew names with letters and numbers written beside them. Among the most intriguing elements is a partially preserved name that caught the attention of researchers: “Shimon.”

One line includes the end of the name ‘Shimon’ followed by the Hebrew letter mem, and in the other lines are symbols representing numbers. Some of the numbers are preceded by their economic value, marked with the Hebrew letter mem, an abbreviation of ma’ot (Hebrew for ‘money’), or with the letter resh, an abbreviation of reva’im (Hebrew for ‘quarters’).

This ancient accounting system reveals sophisticated record-keeping practices that mirror modern commercial transactions. The use of abbreviations for monetary denominations suggests a standardized system of commerce that would have been familiar to merchants and customers throughout the region.

While four other similar Hebrew inscriptions have been documented in Jerusalem and Bet Shemesh, all marking names and numbers carved on similar stone slabs and dating to the Early Roman period, this is the first inscription to be revealed within the boundaries of the city of Jerusalem at that time. This distinction makes the find particularly significant for understanding urban commerce during the Second Temple period.

The inscription’s location within the ancient city limits provides direct evidence of commercial activity in the heart of Jerusalem, rather than in outlying areas or burial sites where similar inscriptions have previously been found.

According to the researchers, the inscription was carved with a sharp tool onto a chalkstone (qirton) slab. The stone slab was initially used as an ossuary (burial chest), commonly used in Jerusalem and Judea during the Early Roman period (37 BCE to 70 CE).

This repurposing of burial equipment for commercial purposes reveals practical aspects of ancient life that are rarely preserved in the archaeological record. While ossuaries are generally found in graves outside the city, their presence has also been documented inside the city, perhaps as a commodity sold in a local artisan’s workshop or store.

The transformation of this ossuary lid into a business ledger suggests either economic necessity or the practical reuse of available materials—a practice common in the ancient world, where stone surfaces suitable for writing were valuable commodities.

The intriguing find was discovered in the lower city square, located along the Pilgrimage Road. This Road, extending approximately 600 meters, connected the city gate and the area of the Siloam Pool in the south of the City of David to the gates of the Temple Mount and the Second Temple, serving as the main thoroughfare of Jerusalem at the time.

The importance of the Pilgrimage Road cannot be overstated. As the primary artery connecting the southern entrance of Jerusalem to the Temple Mount, it would have witnessed constant foot traffic from pilgrims, merchants, and residents. This unique discovery aligns with similar findings uncovered in the area, underscoring the commercial nature of the region.

Archaeological evidence from the vicinity includes measuring tables and other commercial implements, painting a picture of a bustling marketplace that served both religious pilgrims and local inhabitants.

The stone tablet was retrieved from a tunnel of a previous excavation at the site, which was dug at the end of the 19th century by British archaeologists Bliss and Dickie. They excavated tunnels and pits along Stepped Street. This connection to earlier archaeological work adds layer of historical continuity to the find.

Although the inscription was found out of its original archaeological context, it was possible to date it to the Early Roman period, at the end of the Second Temple period, based on the type of script, the type of stone slab, and its similarity to other contemporary inscriptions.

The dating methodology employed by the researchers demonstrates the sophisticated techniques available to modern archaeologists. By analyzing paleographic features (the style of writing), material composition, and comparative examples, they were able to place this inscription within a specific historical timeframe despite its displaced context.

The significance of this discovery extends far beyond its monetary notations. As the researchers note, “the everyday life of the inhabitants of Jerusalem who resided here 2,000 years ago is expressed in this simple object. At first glance, the list of names and numbers may not seem exciting, but to think that, just like today, receipts were also used in the past for commercial purposes, and that such a receipt has reached us, is a rare and gratifying find that allows a glimpse into everyday life in the holy city of Jerusalem”.

This perspective highlights how archaeological discoveries can bridge the gap between ancient and modern life. The fundamental human need to record transactions, track debts and credits, and maintain business records has remained constant across millennia.