Israel’s governing coalition is considering legislation that would significantly restrict eligibility for citizenship under the Law of Return, potentially affecting one of the foundational expressions of Israel’s identity as a Jewish state.

The controversial bill, authored by right-wing lawmaker Avi Maoz of the Noam party, would eliminate a provision that extends immigration rights to individuals who have at least one Jewish grandparent but are not considered Jewish under religious law. An estimated 500,000 Israelis have immigrated to the country since 1970 under this so-called “grandparent clause.”

The Ministerial Committee for Legislation discussed the proposal on Sunday but decided to postpone further debate for one month. With the Knesset entering recess until October, the bill is unlikely to advance in the near future. The committee also delayed consideration of a second Maoz bill that would ban discussion of LGBTQ issues in classrooms.

The Law of Return was established in 1950, two years after Israel’s founding, granting every Jew worldwide the automatic right to immigrate to the Jewish state. The law was expanded in 1970 to include grandchildren of Jews, partly in response to the Nazi Nuremberg Laws, which had targeted anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent for persecution.

“In its current form, the Law of Return allows even the grandson of a Jew to receive immigrant status and rights, even if he himself, and sometimes even his parents, are no longer Jewish,” Maoz wrote in the bill’s explanatory notes. “This situation means that the law is being exploited by many who have severed all ties with the Jewish people and their traditions.”

The proposal has garnered support from other coalition members, including Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and Likud lawmaker Shlomo Karhi, who have introduced similar bills in recent years. Israel’s haredi Orthodox parties, also part of Netanyahu’s coalition, have historically opposed the grandparent clause.

Under traditional Jewish law (halakha), a person is considered Jewish only if their mother is Jewish or if they formally convert to Judaism through Orthodox channels. Religious parties have long sought to limit conversion authority to Orthodox rabbis.

However, supporters of the current law argue that the grandparent clause upholds Israel’s role as a refuge for anyone with Jewish ancestry, particularly those excluded by Orthodox definitions. The provision has been especially important for welcoming immigrants from the former Soviet Union, where decades of religious suppression left many unable to meet strict religious criteria while maintaining deep connections to their Jewish heritage.

Diaspora Jewish organizations and non-Orthodox movements strongly support maintaining the grandparent clause. Stuart Weinblatt, a prominent Conservative rabbi and chairman of the Zionist Rabbinic Coalition, emphasized the global implications of such changes.

“There are other issues, which have an impact on Jewish peoplehood, which is worldwide, and it’s important to consider the wider consequences,” Weinblatt said. He advocates for embracing prospective immigrants rather than closing doors, arguing that “we should be welcoming them back into the fold, capitalizing on their desire to make their future in the homeland of the Jewish people.”

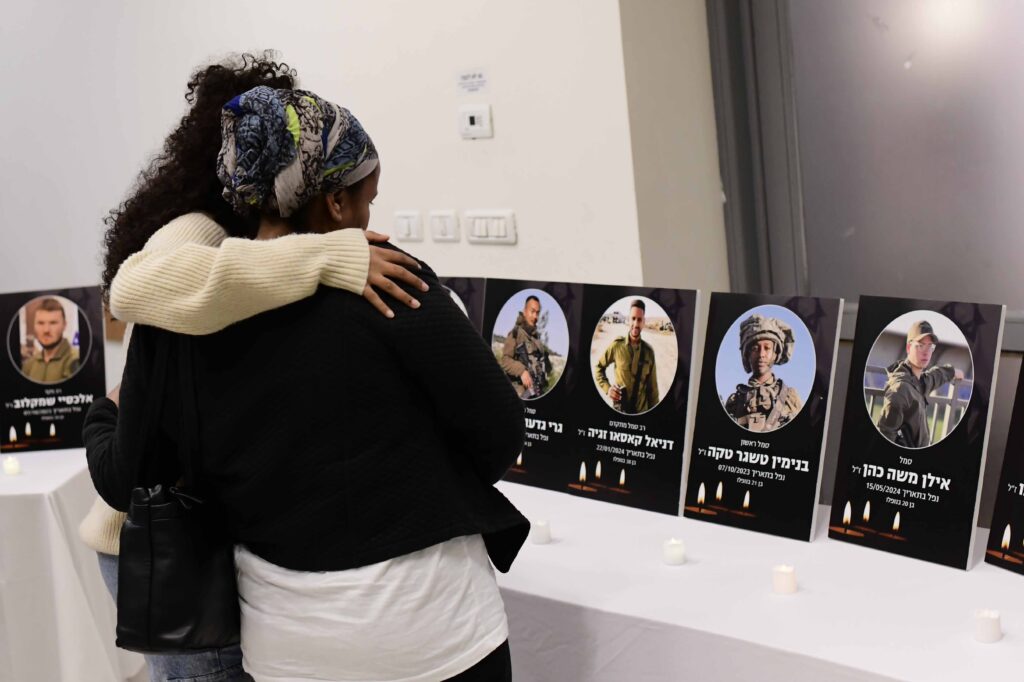

The proposal comes at a sensitive time, with thousands of immigrants who may not be considered Jewish under religious law currently serving in Israel’s military. Rabbi Seth Farber, director of the ITIM nonprofit that helps Israelis navigate religious bureaucracy, called the timing “deeply troubling.”

“At a time when thousands of immigrants — some not halachically Jewish — are showing courage and sacrifice on the battlefield, it is morally absurd for government officials, many of whom never served in the IDF, to question their right to belong,” Farber said.

Maoz quit Netanyahu’s coalition in March, protesting what he described as the government’s failure to advance a sufficiently Orthodox and nationalist agenda. Despite his departure from the coalition, his bills continue to receive consideration by the ministerial committee.

The debate reflects broader tensions within Israeli society about religious authority, national identity, and the balance between maintaining Jewish character and remaining inclusive to those with Jewish ancestry. As the proposal moves forward, it will likely face significant opposition both domestically and internationally, particularly from Jewish communities worldwide who view the Law of Return as a crucial safeguard for Jewish refugees and immigrants.

The Law of Return, enacted by Israel on July 5, 1950, grants all Jews the right to immigrate to the country and obtain immediate citizenship. When Ben Gurion submitted the Law of Return to the Knesset for its approval, he argued that the rights granted to Jews—and only to Jews—in the Law of Return were not given to them by the state. These rights predated the state, and Jews had possessed them by virtue of being Jews. The law emerged as a foundational pillar of Israel’s identity as a Jewish homeland, reflecting the historical connection of the Jewish people to the land despite centuries of diaspora.

The original 1950 law was relatively straightforward, but it quickly became the subject of intense legal and theological debate. The most significant expansion came in 1970 when the law was amended to include not only Jews but also their children, grandchildren, and spouses, even if they were not Jewish according to religious law. This “grandparent clause” was partly a response to the Nazi Nuremberg Laws, which had targeted anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent for persecution.

The law has generated numerous controversies that continue to shape Israeli society and politics today. The most famous early case was that of Brother Daniel (Oswald Rufeisen), a Polish Jew who converted to Catholicism and became a Carmelite monk. When Brother Daniel applied for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return in 1958, his application created an unprecedented legal dilemma. The Ministry of Interior rejected his application, arguing that as a converted Catholic, he was no longer eligible for automatic citizenship as a Jew. In December 1962, the Supreme Court of Israel rejected the claim of Brother Daniel, ruling that the Law of Return does not include Jews who practice another religion. This case established the principle that Jewish identity for immigration purposes required not just ethnic or ancestral Jewish background, but also maintaining Jewish religious identity.

The Law’s definition of a “Jew” and “Jewish people” is subject to debate. Israeli and Diaspora Jews differ with each other as groups and among themselves as to what this definition should be for the Law of Return. The 1970 amendment sparked ongoing debates about the interpretation of “Who is a Jew” under Israeli law. While the amendment provided a broad definition, tensions persist, particularly between different Jewish denominations (Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform).

Another major controversy emerged around conversion recognition. Then in 1989, the Supreme Court ruled that anyone who converted to Judaism in a non-Orthodox conversion outside the State of Israel is included in the Law of Return. Orthodox leaders, particularly the Israeli rabbinate, were outraged at the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Much of the debate among the religious parties in Israel was that the amendment recognized Reform and Conservative conversions to Judaism that were performed outside the State of Israel. This created ongoing tension between Israel’s Orthodox establishment and non-Orthodox Jewish movements worldwide, with religious parties continuously seeking to limit conversion authority to Orthodox rabbis only.

These controversies reflect more profound questions about Jewish identity, religious authority, and the balance between Israel’s role as a refuge for all Jews and its character as a Jewish state defined by religious law. The current debate over the grandparent clause represents the latest chapter in this ongoing struggle over who has the right to call Israel home.