Visiting the shrine that both Jews and Druze believe is Jethro’s tomb.

On a recent hike in the southern Galilee, I got to see up close how well Jews and Druze get along—something that honestly amazes me every time I think about it.

This is Nabi Shuaib, the holiest place in the world for the Druze, sitting right behind Mount Arbel’s gorgeous view of the Kinneret. Both Druze and Jewish traditions going back at least to the 13th century say the shrine inside this building (under the white dome) is where Jethro is buried—yes, Moses’ father-in-law.

If you know Exodus 18, you’ll remember Jethro. He was the priest of Midian who gave Moses crucial advice when Moses was overwhelmed trying to settle every dispute among the Israelites personally. “Choose capable men who fear God,” Jethro counseled, “trustworthy men who hate dishonest gain.” Then establish officials over thousands, hundreds, fifties and tens. Jethro essentially created the judicial system we still use today.

What’s remarkable is that Jethro isn’t just a biblical figure to the Druze—he’s one of their most revered prophets. They call him Shu’eib, and he represents an important connection between Jewish and Druze peoples.

That connection became painfully clear almost a year ago when Hezbollah rockets struck a soccer court in Majdal Shams, killing twelve children. The attack was devastating, but it also highlighted something important: the deep bond between Israel’s Druze community and the Jewish state they serve.

The relationship Jews have with our Druze neighbors is genuinely remarkable. They speak Arabic, and on the surface you might think we don’t have much in common. But we’ve developed an extraordinary partnership—far stronger than with other Arab communities. The key difference: unlike Muslim and Christian Arab citizens, Druze men are drafted into the IDF alongside their Jewish counterparts. And they don’t just serve—they excel, rising to top ranks and serving in elite combat units.

There are about 149,000 Druze in Israel today. Their religion started back in 1017 CE, growing out of Islam but going in its own direction under this mysterious leader called Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in Egypt. After 26 years, they closed the door—no more converts, ever. That makes them one of the world’s most exclusive religions. They actually prefer calling themselves “al-muwahhidun”—believers in the One God.

Why are they so loyal to Israel? Their faithfulness stems from a core religious principle: absolute loyalty to the state where they live. This devotion has come at great cost. Nearly 500 Druze soldiers have died defending Israel since 1948. Just this past year, we lost heroes like Lt. Col. Salman Habaka, who fell in Gaza after leading his battalion into Kibbutz Be’eri on October 7.

So when I was in the area several weeks ago, making my rounds praying for peace and healing in Israel at the graves of many of Jewish history’s holiest teachers, I made sure to stop by Nabi Shuaib.

As I walked up the stairs to this possibly 3,000-year-old shrine, I was greeted by a dozen Druze kids (no security guards anywhere) who pointed me upward toward the tomb at the top of the complex. When I got to the roof, they told me—in fluent Hebrew—to talk to a certain elderly man sitting in an office.

I wished the man good afternoon and asked if I could pray at the grave. After looking me over, he motioned to a bench and told me to sit and take off my shoes. Walking on the stone floor in my socks, I felt a bit closer to Jethro’s legacy: his son-in-law was told by God to remove his shoes when he visited the burning bush outside of Egypt.

When we reached the tomb-room, my minder pointed to a long stone (or was it wood?) beam at the foot of the door (imagine a doorframe with four sides). He told me to hop over the beam without touching it, with his gaze suggesting that disobeying would quickly turn me into an enemy of the Druze. I was happy to follow instructions: I like when other people respect my religion, so why shouldn’t I respect theirs?

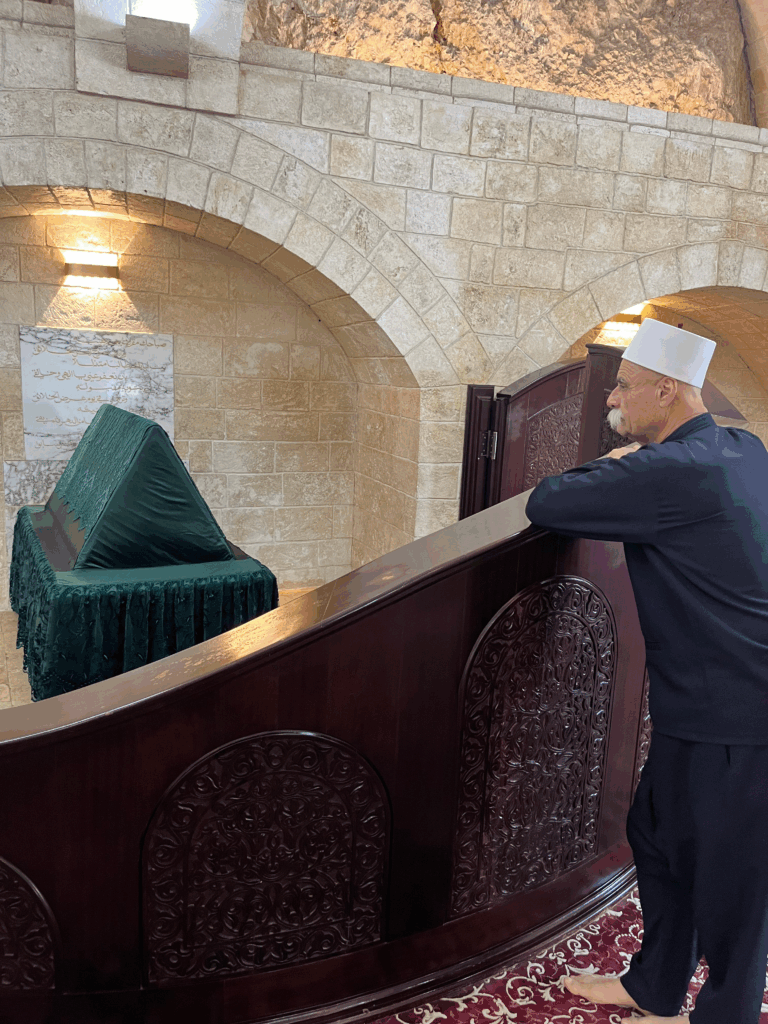

Inside the dimly lit shrine, I saw a young boy praying (or maybe meditating?), and a few elderly women talking in the adjacent room. My minder kept a respectful distance but never stopped watching me as I prayed for peace and healing for all of Israel’s citizens—Jews and Druze together.

I asked him if I could take pictures. He gave a curt nod, so I quickly snapped away, even taking this selfie-of-sorts together with him.

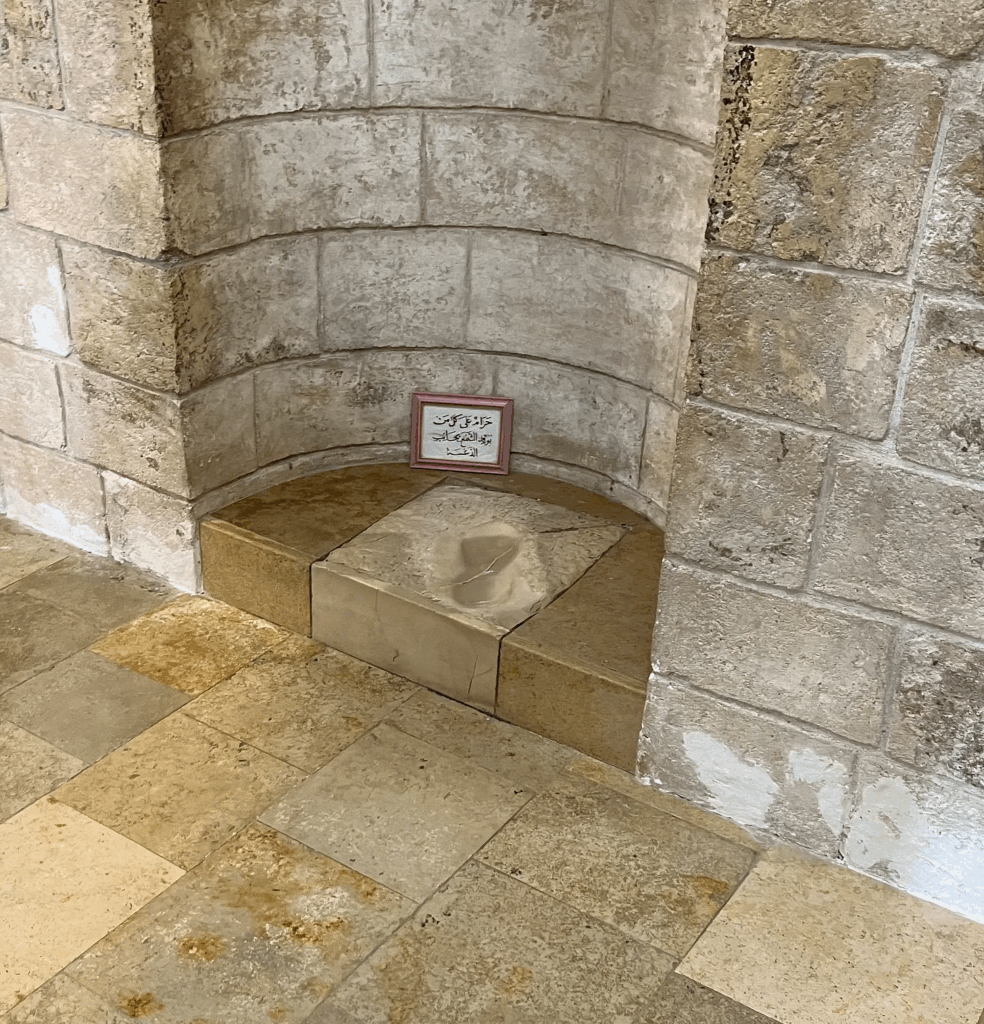

As I got ready to leave, he nodded toward a footprint embedded in a stone in the corner.

Wow, I thought! There it is, for real!

I had read centuries-old testimonies from Jewish visitors to this shrine who had been told by their Druze minders (they’ve been here awhile) that this imprint was made by Jethro himself. (Hey, why not?)

On my way out, I again gingerly hopped over the stone beam. After putting my shoes back on, I hopped down to the Arbel cliffs to pick up my bus home from Tiberias.

This visit reminded me that in a region where ancient conflicts persist, the friendship between Jews and Druze offers genuine hope. Built on mutual respect, shared sacrifice, and devotion to this land, it proves that different faiths can work together and flourish. As Majalli Whbee, the former deputy speaker of the Knesset, expressed it: “Together we will stay forever.”

Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Naiman is a foraging guide and certified health counselor. He serves as a spiritual mentor in Yeshivat Lev HaTorah of Ramat Beit Shemesh, where he teaches a daily Healthy Jew class. He recently published a book, Land of Health: Israel’s War for Wellness, and writes a weekly newsletter, Healthy Jew. Learn more at healthyjew.org, and reach out at contact@healthyjew.org.