A recent article in MIT Technology Review highlighted research by three Stanford University scientists exploring the creation of “bodyoids” – lab-grown human bodies developed from pluripotent stem cells, engineered without brains to prevent consciousness and pain. These bodyoids would serve as organ banks, potentially addressing critical shortages in transplantable human tissues and organs. The researchers argue that without neural components, these creations lack the ability to think, feel, or suffer, providing a potential ethical advantage over current animal-based research models.

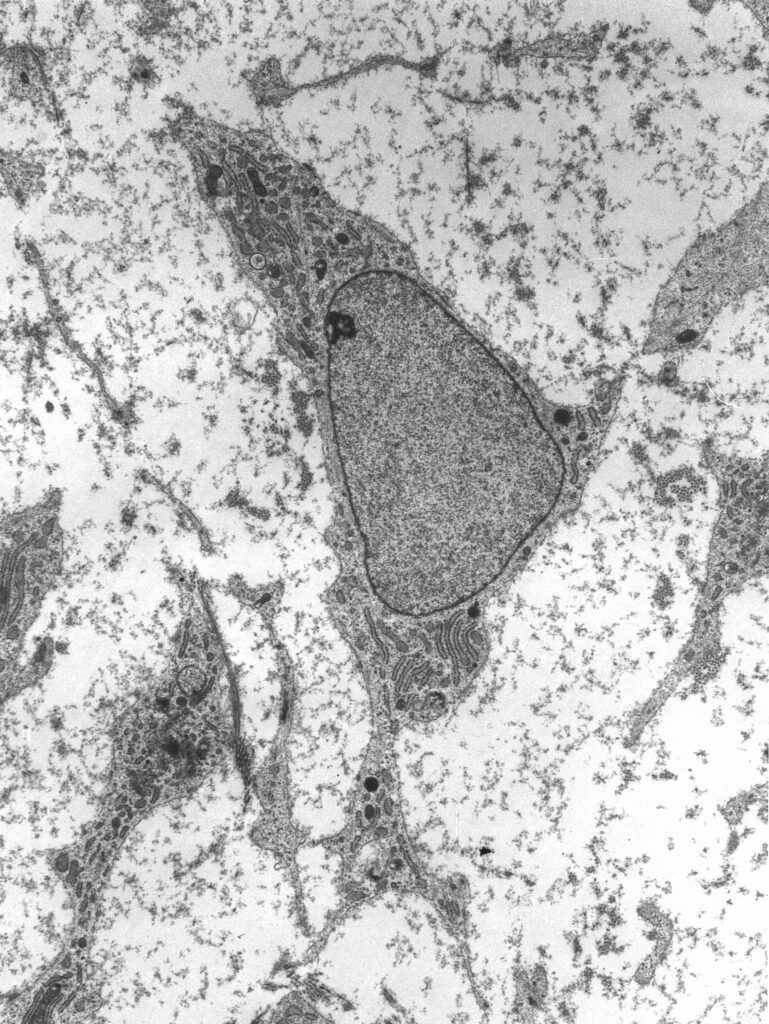

Bodyoids represent a promising but still theoretical advancement. They are human bodies developed entirely outside the womb, using stem cells and artificial gestation technologies, but without neural components. This approach could offer a limitless, personalized supply of organs and tissues for transplantation, potentially eliminating the need for animal testing, reducing organ waiting lists, and enabling precise drug screening with minimal rejection risks.

Advances in biotechnology, including artificial wombs and stem cell research, have brought this concept closer to reality. For instance, scientists have recently recreated early stages of human embryo development using stem cells. These breakthroughs suggest the possibility of producing living human bodies without the neural structures that enable consciousness.

However, the researchers acknowledge significant challenges. Current US regulations, like the “14-day rule,” restrict human embryo research beyond 14 days, preventing the development of mature bodyoids. The 15th day marks the start of gastrulation, when the primitive streak forms and germ layers differentiate – a crucial step in natural embryonic development.

As this research advances, the ethical and social challenges are likely to be as significant as the technical ones. Even if the creation of bodyoids becomes scientifically feasible, careful consideration will be required to determine whether it should be pursued, both for nonhuman and human forms.

Rabbi Moshe Avraham Halperin of the Machon Mada’i Technology Al Pi Halacha (the Institute for Science and Technology According to Jewish Law) speculated that scientists could not succeed in “creating a human with consciousness.”

“Scientists can rearrange but cannot create something from nothing, as God did in Genesis,” Rabbi Halperin said. “Scientists are merely combining and manipulating existing material. We know that the Bible forbids actual Creation. And the Bible states that men can’t create a new life in any case, as only God has that ability. Even the greatest atheists have been unable to refute this.”

“If scientists ever do develop the ability to create life, Torah law explicitly prohibits this,” he said. “But that would require creating a being that can think and speak. Life is not enough to classify a being as a Man. The rabbi explained that such a creature, alive but without independent thought or the ability to communicate, would be classified as a golem; an animated, anthropomorphic being in Jewish folklore, which is entirely created from inanimate matter, usually clay or mud.”

Rabbi Halperin noted that the scientists are working on the basic assumption that consciousness, or soul, is located exclusively in the brain.

“They may grow bodies in a lab and claim that they are refraining from growing a brain for ethical reasons but the fact is they simply cannot make something in a lab that has consciousness, awareness, or will be able to express independent thoughts.”

“In Kabbalah, we understand that the most basic level of consciousness and soul, what we call the nefesh, is found even in animals, even a mosquito,” Rabbi Halperin explained. “Scientists can grow organs, but anything that has any level of soul or consciousness, they cannot make in a laboratory. They can grow or clone, but make from basic cells, they cannot do so.”

“In Man, the nefesh is our base instincts and drives. This is found in our physicality, our biology. What we call neshama, the ‘soul’, is transcendent, not limited to the brain or our physicality. This is our drive and our ability to act in this world on a higher level. This gives us the ability to speak in a coherent manner, to express thoughts. This is connected always to God.”

Despite these hurdles, the potential benefits are significant. Bodyoids could provide personalized drug testing, eliminate organ rejection risks, and reduce dependence on animal testing, addressing critical gaps in medical research. However, this technology also raises ethical concerns. Would these creations challenge our understanding of personhood? Could they diminish respect for people with disabilities, or blur the line between human and nonhuman life?

The authors urge careful consideration of these questions, suggesting that early efforts should focus on non-human bodyoids to refine techniques and address ethical implications before human trials begin. They stress the importance of public dialogue to navigate the ethical landscape as this technology develops.

While bodyoids remain a distant prospect, the researchers argue that the potential to save lives and reduce suffering makes this an idea worth pursuing, despite the profound ethical questions it raises.