Sutures and operations have been around for five millennia. Until the 1840s, patients underwent extreme suffering because there was no anesthesia, and many did not survive operations. Then, in 1846, a young dentist in Boston, Dr. William T.G. Morton, and Massachusetts General Hospital surgeon Dr. John Collins Warren, discovered that there was a gas called ether that when inhaled in the proper dose provided safe and effective anesthesia.

Current surgical procedures involve the cutting of the human body by the surgeon, doing what needs to be done, and sewing the wound shut – an invasive procedure that harms surrounding healthy tissue and often leaves scars. Some sutures dissolve by themselves as the wound heals, while others need to be manually removed.

Sterile dressing is then applied over the wound, and medical personnel monitor the wound by removing the dressing to allow observation for signs of infection like swelling, redness and heat. This procedure is painful to the patient and disruptive to healing, but it is unavoidable.

Working with these methods also means that infection is often discovered late since it takes time for visible signs to appear, and more time for the inspection to come round and see them. In developed countries, with good sanitation available, about one-fifth of patients develop infections after their operation, requiring additional treatment and lengthening recovery time. The situation is much worse in developing countries. New technology was needed to overcome these suture challenges.

Prof. Hossam Haick, a world expert in the field of medical nanotechnology and non-invasive disease diagnosis at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, and his team have found a better way to deal with wounds and replace sutures. So far, Haick and colleagues have more than 42 patents and patent applications, and he has initiated startup companies to commercialize innovative non-invasive technology for monitoring vital signs in health.

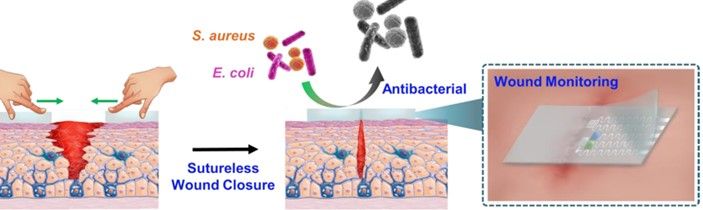

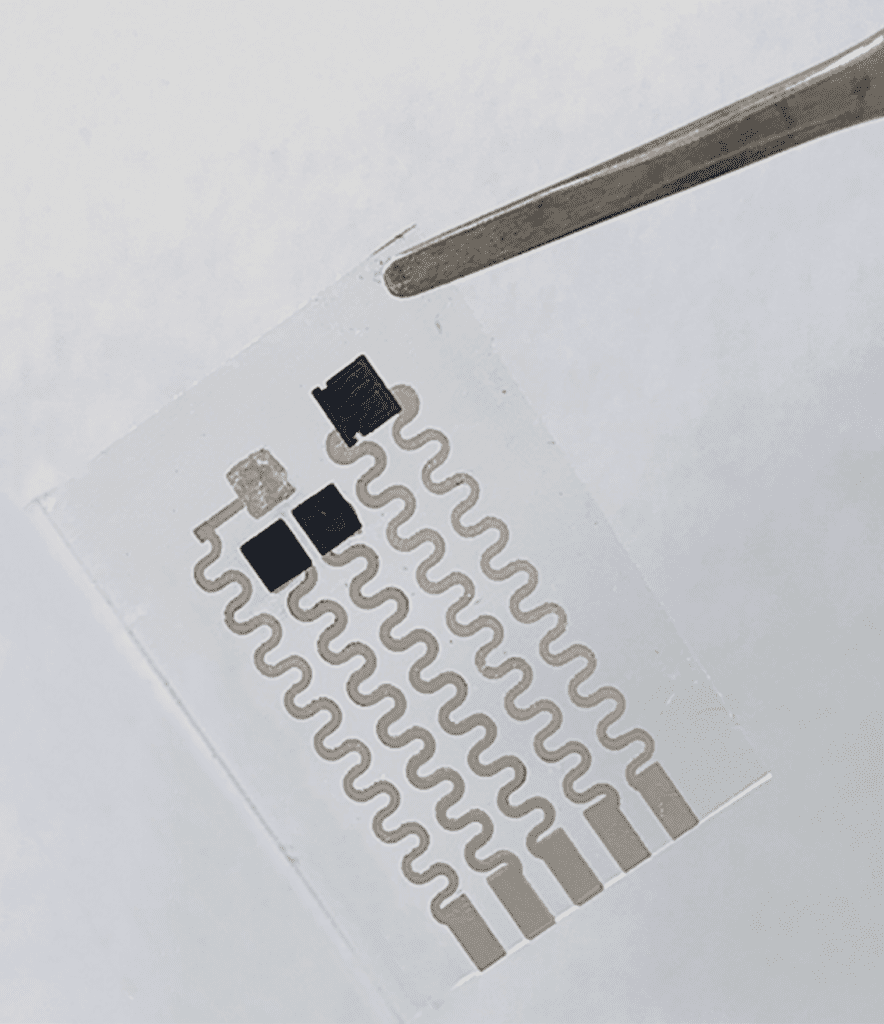

Prior to beginning a procedure, the dressing – which is very much like a smart band-aid – developed by Haick’s lab is applied to the site of the planned incision, which is then made through the dressing. After the surgery, the two ends of the wound will be brought together, and within three seconds the dressing will bind itself together, holding the wound closed, similarly to sutures. From then, the dressing continuously monitors the wound, tracking the healing process, checking for signs of infection like changes in temperature, pH, and glucose levels. It also reports to doctors’ and nurses’ smartphones or other devices. The dressing also itself releases antibiotics onto the wound area, preventing infection.

“I was watching a movie on futuristic robotics with my kids late one night,” Haick, “and I thought, what if we could really make self-repairing sensors?” It seemed impossible.

But the next day, Haick, who, the very next day after his Eureka moment, was researching and making plans. The first publication about a self-healing sensor came in 2015, with the professor’s colleague Dr. Tan-Phat Huynh. At that time, the sensor needed almost 24 hours to repair itself. By 2020, sensors developed with doctoral student Muhammad Khatib were healing in under a minute, but while it had multiple applications, it was not yet biocompatible, that is, not usable in contact with skin and blood. Creating a polymer that would be both biocompatible and self-healing was the next step, and one that was achieved by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Ning Tang.

The new polymer is structured like a molecular zipper, made from sulfur and nitrogen: the surgeon’s scalpel opens it; then pressed together, it closes and holds fast. Integrated carbon nanotubes provide electric conductivity and the integration of the sensor array. In experiments, wounds closed with the smart dressing healed as fast as those closed with sutures and showed reduced rates of infection.

The self-healing elastomer contains cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and has high mechanical toughness, biocompatibility and outstanding antibacterial activity, enabling the wound dressing to effectively inhibit bacterial growth and accelerate infected wound healing. In vivo tests in the lab based on a full-thickness skin incision model showed that the multifunctional wound dressing can help in contracting wound edges and facilitate wound closure and healing, as could be evidenced by notably dense and well-organized collagen deposition.

“It’s a new approach to wound treatment,” concluded Haick. “We introduce the advances of the Fourth Industrial Revolution – smart interconnected devices, into the day-to-day treatment of patients.”

The team’s article has just been published in the journal Advanced Materials under the title “Highly Efficient Self-Healing Multifunctional Dressing with Antibacterial Activity for Sutureless Wound Closure and Infected Wound Monitoring.”

The team’s article has just been published in the journal Advanced Materials under the title “Highly Efficient Self-Healing Multifunctional Dressing with Antibacterial Activity for Sutureless Wound Closure and Infected Wound Monitoring.”